By Robby Ching and Debra Boggs

- Should technology be used as a solution to problems in nature?

- What are some dangers of the metaverse, especially for young people?

- What are the stories only I can tell the world?

- How is plastic pollution affecting us and our future as individuals, communities, and globally?

- What is the role of a citizen in addressing the wrongs of their government?

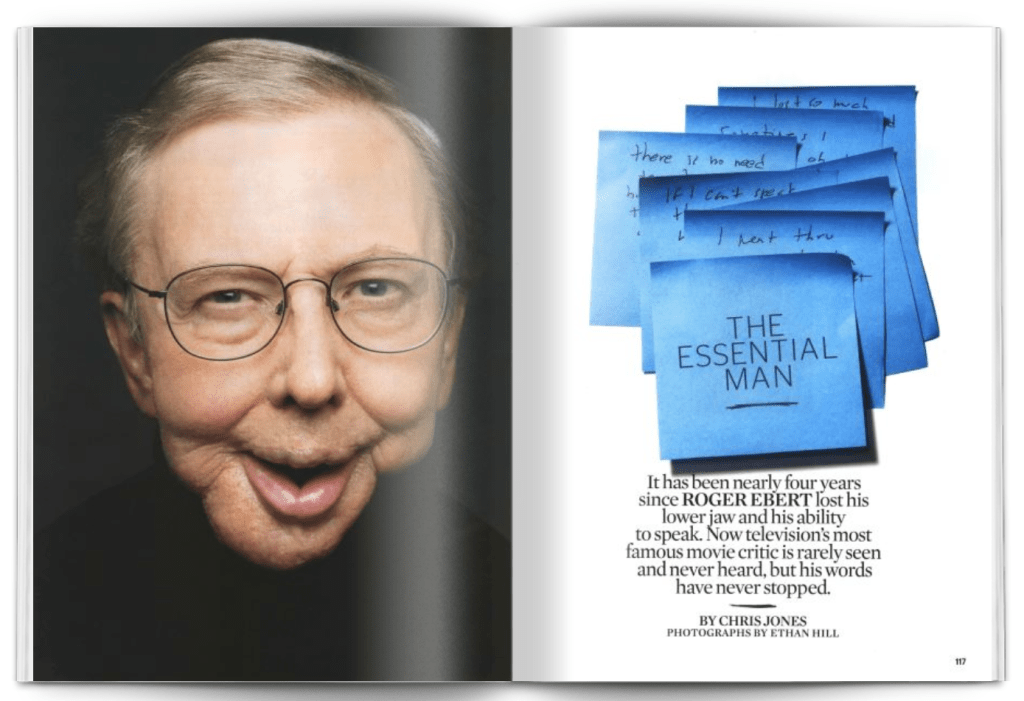

- How can words and images work together to communicate information or tell a story?

- How can stories help us deal with the problems we are facing?

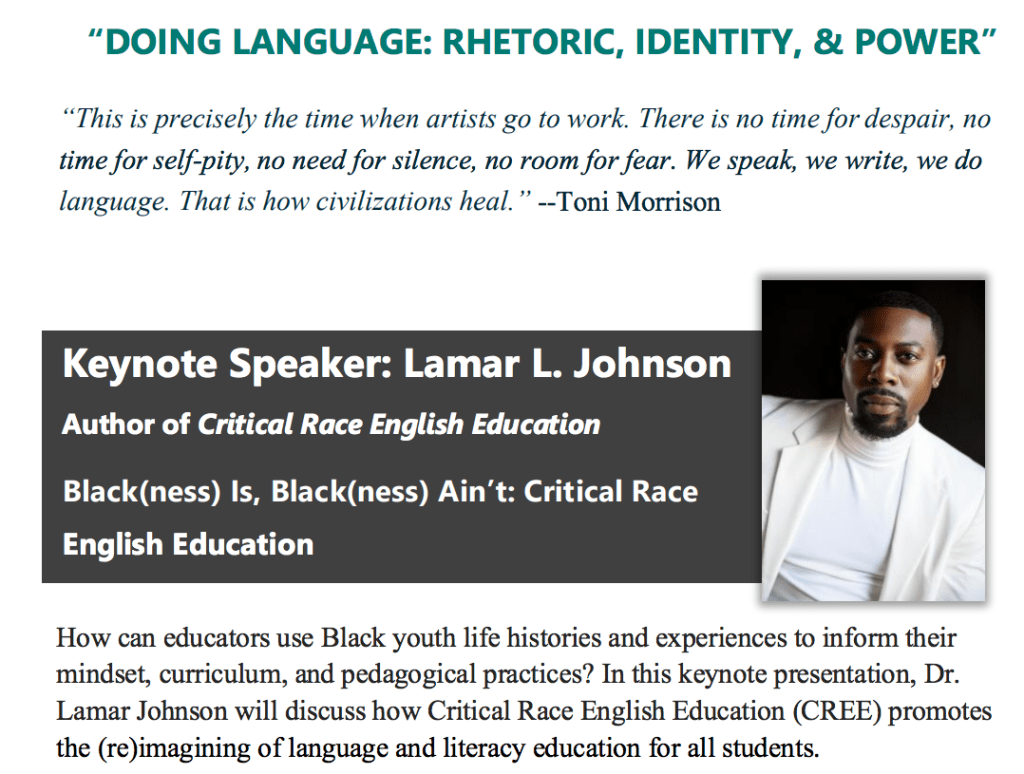

These are a few of the compelling questions that students grapple with as they read, discuss, and view the texts that form the basis for the new ERWC-ELD middle school modules. The modules guide students in reading complex texts across a range of genres, including novels, memoirs, graphic novels, TED Talks, interviews, and articles.

These modules are being rolled out on June 23 at the ERWC Literacy Conference in Long Beach. After that, they will be available to teachers across the state who have participated in professional learning to guide their implementation.

These modules implement the vision of the California Framework for English Language Arts (ELA) and English Language Development (ELD) and support teachers in creating instruction that meets the California Common Core Standards (CCCS) and the California ELD Standards. The modules are designed for ELA with Integrated ELD classes linked to Designated ELD classes but are adaptable for ELA only or ELD only classes. They are also intended to be customized depending on the teaching situation and the place students are in their literacy development.

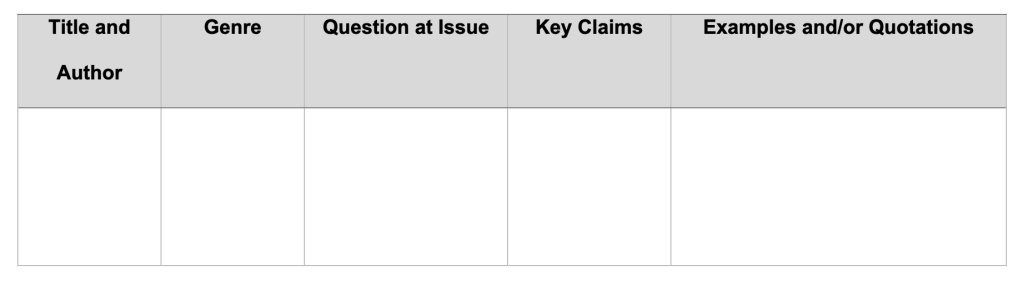

The modules include whole books and shorter texts that raise complex issues and employ complex language. Recognizing that students require guidance and support as they learn to make meaning of these texts, module writers have built in a variety of scaffolds to ensure that all students, including English learner (EL) students, build their reading stamina and productively with the texts that are central to the modules. Students practice applying the strategies of expert readers to understand and analyze these texts and then create texts of their own, producing many of the genres they have experienced as readers. They collaborate to produce a TED Talk, write a micro-memoir, produce a slide show with presenter notes, deliver a speech at a climate summit, and create an infographic.

The language-focused activities in the modules foster English Learner (EL) and Multilingual Learner (ML) students’ understanding of how English works at the word, phrase, clause, and text level while supporting disciplinary literacy growth for all students. The language-focused instruction is offered in the context of the texts students are reading as they participate in engaging and collaborative activities. Many activities implement high-impact strategies that have been shown to be especially effective in this literacy development, building students’ awareness of how writers and presenters make choices about the language they use depending on who their intended audience is and how they hope to impact that audience.

Analyzing Mentor Texts

As they experience these modules, middle school students are introduced to the foundation of a rhetorical approach to reading, writing, and language. As part of this approach, in each module, students analyze mentor texts that model the form, the rhetorical strategies, and the language required by the culminating task. During this analysis of mentor texts, students develop a shared understanding of what is required for a specific kind of text to be successful. The teacher provides or they work together to create success criteria they can use to guide their drafting, and which can be used for peer feedback as well as grading.

Although each module reflects the expertise of its individual writers, they take a common pedagogical approach reflected in “Essential Pedagogies for Integrated and Designated English Language Development in ERWC,” available in the ERWC Online Community. Best practices for English Language Development suggest that students learn best by collaborating with other students, an understanding reflected in the California ELD Standards. The ERWC-ELD middle school curriculum assumes student-centered classrooms where students are constantly interacting with each other around the texts and tasks of the modules.

These modules do not make up an entire curriculum. Including assignment sequences from textbooks or other sources will be needed to create a full year-long curriculum. But the rhetorical approach embedded in these modules enables middle school teachers to apply a similar approach to all the texts they teach. The High Impact Strategies Toolkit, available on the home page of the ERWC online community, provides a rich source of proven protocols to craft instruction, following the full ERWC arc from the professional text to the student text, and from rhetorical reading to rhetorical writing.

Experiencing these ERWC-ELD modules in middle school invites students to cross the threshold to becoming rhetorical readers and writers as they discover that writers create texts in particular contexts, for particular audiences to achieve particular purposes. These students will leave middle school having acquired a portfolio of reading and writing strategies to apply in their high school ERWC classes, in other academic classes, and in the wider world.

Works Cited

California Department of Education, California Common Core State Standards: English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects. Sacramento, CA: Adopted by California State Board of Education August 2010 and modified March 2013.

California Department of Education (CDE), California English Language Development Standards: Kindergarten Through Grade 12. Sacramento, CA: Adopted by California State Board of Education November 2012, CDE 2014.

Fletcher, J. (2015). Teaching arguments: Rhetorical comprehension, critique, and response. Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers.

The Expository Reading and Writing Course, 3rd ed. (2019). California State University Press. Long Beach CA.

–Katz, M., Graff, N., Unrau, N., Crisco, G., and Fletcher, J. “The Expository Reading and Writing Course (ERWC) Theoretical Foundations for Reading and Writing Rhetorically” (2020).

–Ching, R., (2021). “Essential Pedagogies for Integrated and Designated English Language Development in ERWC.”

— Arellano A., Ching, R., Boggs, D., and Spycher, P. (2021) “The High Impact Strategies Toolkit to Support Students in ERWC Classrooms” in The Expository Reading and Writing Course (3.0). California State University Press. Long Beach CA.

About the Author:

Debra Boggs is a retired educator. She taught high school English and worked as a school and county office administrator. She is a member of the ERWC Steering Committee and part of the leadership team that created ERWC-ELD modules for grades 9-12. She is also currently a member of the team that created the new ERWC-ELD middle school modules for grades 6-8.

Roberta Ching is a Professor Emerita in English at California State University, Sacramento. She coordinated the English as a Second Language program at CSUS before becoming chair of the Learning Skills Department. She was a member of the original 12th Grade Task Force and is currently a member of the team that created the new ERWC-ELD middle school modules for grades 6-8. She serves on the ERWC Steering Committee.

To learn more about ERWC or how to access this free curriculum, please visit https://writing.csusuccess.org/.

Editor’s Note: The 2025 ERWC Literacy Conference will be June 23rd in Long Beach, California. Our theme this year is “Leaning into Liminality: A Return to Language, Wonder, and Inspiration.” Registration is free! Please visit the ERWC Online Community for more information.