By John Edlund

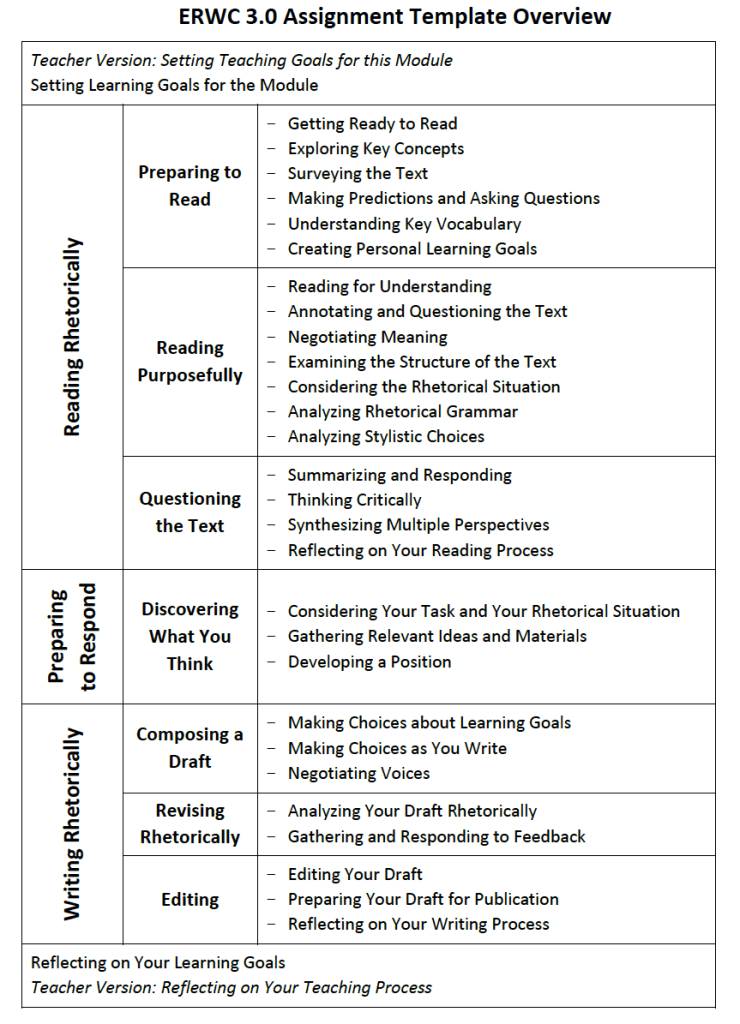

In late November 2022, a company called OpenAI opened public access to an AI called ChatGPT. Those who sign up for an account can ask it questions, give it instructions, and converse with it. The program can do research and write texts in various genres, including essays on any topic imaginable. It can also write and debug computer code. Educators who have tried it are quite impressed with its abilities. Students are already using it to do their homework. How should English teachers respond? Lots of articles have already been written on this question. In general, the advice tends to cluster around four strategies:

- Design AI-proof assignments

- Devise better AI detection practices

- Have students hand write their essays in class

- Help students use the tool wisely and effectively

Of these, the fourth one is probably the most realistic. The first and second have already proven to be difficult, and ChatGPT is not even the most sophisticated AI out there. The third is a big step against the social trend. It may be useful in particular situations, but it is a denial of technological progress rather than an embracing of it, and most students will see it as old-fashioned and backward. Students are going to use the available tools, whatever we say.

The real question, however, is “Why are we teaching the skills we teach?” Here is OpenAI’s mission statement:

OpenAI’s mission is to ensure that artificial general intelligence (AGI)—by which we mean highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work—benefits all of humanity.

That is pretty tricky. Their mission is to benefit humanity by creating systems that outperform humans in “most economically valuable work.” If they succeed, humans would have only non-economically valuable work to do. Or perhaps no work at all. What kind of world would this be?

We often tell students that they need critical reading, writing, and thinking skills for college and career success. What if that is no longer true? What if the AIs are doing all of the intellectual work? The problem then is not about detecting whether or not students are doing the work themselves. It is about motivating them to learn to do things that may have no future instrumental value, at least from their point of view.

Humanity has had discussions like this ever since Plato questioned the effect of literacy on memory in the Phaedrus. With every technology that extends or replaces human abilities something is gained but something is lost. Calculators, word processors, spell check, grammar check, copy and paste, search engines, and many other technologies have been controversial for educators because they streamlined and simplified difficult tasks that teachers labored to teach. It was argued that if we became reliant on these technologies, we would no longer be able to do them without the crutch of the electronic tool. The result? We became reliant. And moved on.

But is it different this time? These previous technologies tended to make humans more productive. ChatGPT’s creators, by expressing their mission as creating systems that “outperform humans at most economically valuable work,” seem to be intent on replacing humans rather than augmenting their abilities. Will this lead to some sort of Brave New World in which humans enjoy endless leisure watching TikTok videos while machines do all the work? This seems unlikely.

For now, it seems to me that the most useful and relevant move would be to assign ChatGPT. Have students submit a prompt to the AI and discuss the results. What did it do? What did it get right? What did it get wrong? What can you learn from what it did?

I have a series of posts on my Teaching Text Rhetorically blog that begins with “What Do Writing Courses Do?” I propose a “Writing Matrix” and then in subsequent posts I extend the matrix. It ends with “Writing Matrix Extension 2.” I used these posts when I was helping new Teaching Associates design their initial courses. I think that whatever we do in response to ChatGPT and AIs to come, we need to keep in mind what we are trying to achieve in our courses. This matrix is a good starting point. But we also need to sell students on the idea that these abilities are important, whatever the AI can do.

A caveat: I was put off by the strategies that OpenAI used in the sign-up process. First it asked for my email and a password. It used a CAPTCHA to determine whether or not I was a bot. Then it sent an email verification to my email account. So far this is typical practice and I didn’t have to give it too much information. However, when I clicked the verification link it asked for my first and last name. When I submitted that it asked for my phone number. I bailed at that point. If I am going to sign up for a service, I think it should be clear from the beginning what information they are going to require.

John Edlund is Professor Emeritus in English at Cal Poly Pomona, now retired. He has a Ph.D. in English from the University of Southern California and has been teaching composition, literature, and rhetoric for more than 40 years. He founded and directed two University Writing Centers, one at Cal State L.A. and one at Cal Poly Pomona. He also chaired the ERWC task force and later the steering committee from 2003 to 2018.