EDITOR’S NOTE: Registration for the 2023 ERWC Literacy Conference closes on Monday, May 22. Reserve your spot now before this event sells out!

By Jennifer Fletcher

Like In-N-Out Burger’s “secret” menu, the ERWC Module Archive offers special options for those in-the-know. Roughly 100 modules have been published over the 20 years of ERWC’s history as a nationally recognized literacy initiative, including dozens of modules in versions 1.0 and 2.0.

There are some terrific first and second edition ERWC modules still available for use. While these modules no longer include the module texts (copyright costs prevent Cal State from renewing permissions for all three editions of the curriculum), most of the reading selections can still easily be found online through their original publishers. For instance, “The Last Meow,” a module about the rising costs of veterinary care, uses a feature article in The New Yorker while “The Undercover Parent,” a module about spyware, uses an op-ed piece from The New York Times.

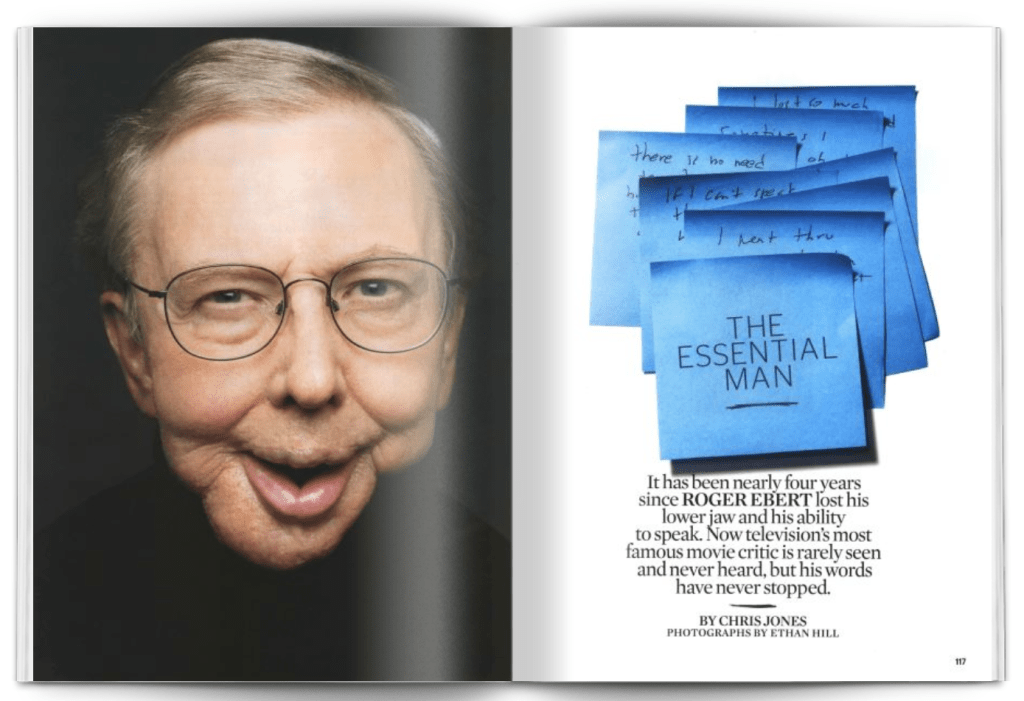

For those of us who have been working with ERWC since its inception in 2003, a visit to the ERWC module archive is a stroll down memory lane. We remember how deeply engaged our students were in analyzing images from an Abercrombie and Fitch marketing campaign, the powerful conversations students had over bell hook’s examination of love and justice, and the moving depiction of Roger Ebert’s transcendent joy following his life-changing battle with cancer. And what veteran ERWC teacher can forget “Bring a Text You Like to Class”?—a perennially popular module on bridging students’ in-school and out-of-school literacies that requires no copyright permissions (aside from those protecting the CSU’s own intellectual property rights).

English departments looking to build a full 9-12 ERWC vertical articulation may find the “secret menu” modules especially appealing, as these can fill gaps in grade 9 and 10 ELA courses. Teachers in other content areas such as social science or in academic preparation programs such as AVID who would like to try out ERWC’s inquiry-based, rhetorical approach to literacy learning may likewise find the older modules useful. Going to the archive could mean not having to compete with the English department for module selections.

While the first and second editions of the curriculum were designed using an older version of the ERWC Assignment Template, ERWC’s focus on developing transferable critical thinking and literacy skills ensures all iterations of the template are enduringly relevant. Each version of the template names the transferable competencies that promote postsecondary success in reading and writing. The recursive literacy process described by the template and enacted through the “ERWC Arc” is imagined in somewhat different ways in each edition of the curriculum, but the goal of the course design remains the same: To support students in developing and internalizing their OWN flexible process for understanding, analyzing, evaluating, and composing texts.

A caveat: Schools that have adopted ERWC grade 11 or 12 under UCOP program status are required to use the 3.0 course descriptions and modules for their approved ERWC courses. ERWC has full courses for grades 11 and 12 and resources for grades 7-10. The resources (i.e., modules and activities) can be used in existing courses such as English 9 without the UCOP restrictions, provided the teachers accessing the materials have been ERWC certified. All teachers must complete 20 hours of ERWC professional learning to gain access to the curriculum.

Jennifer Fletcher is a Professor of English at California State University, Monterey Bay and a former high school teacher. She serves as the Chair of the ERWC Steering Committee. You can follow her on Twitter @JenJFletcher.

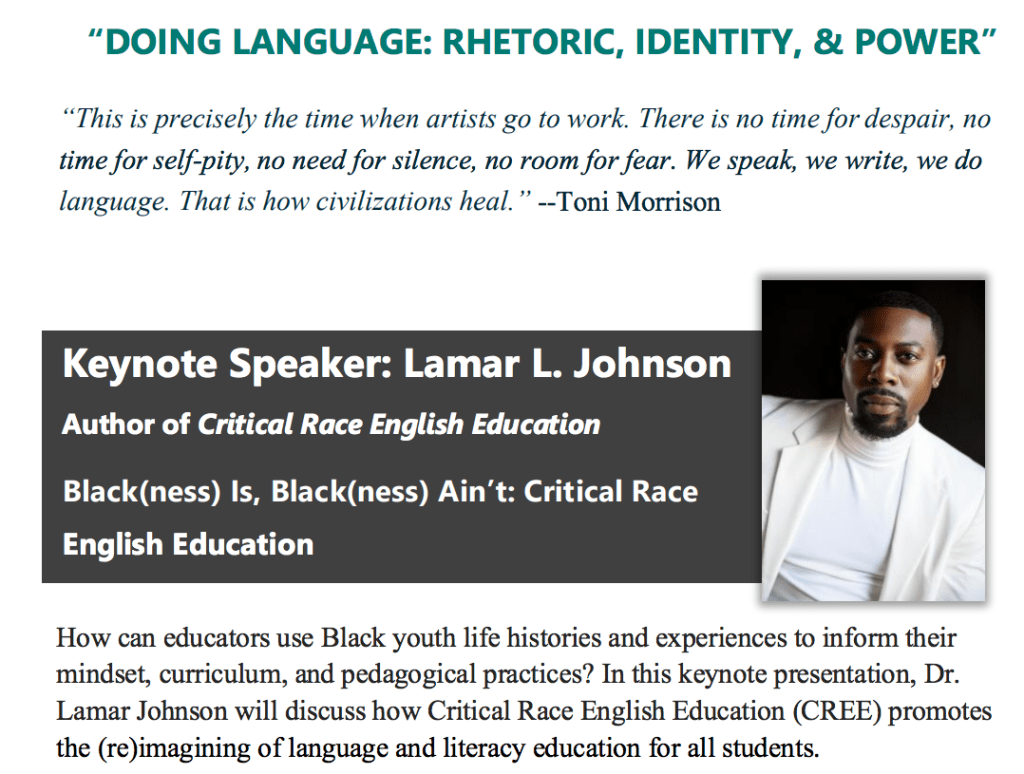

2023 ERWC LITERACY CONFERENCE

June 20 in Sacramento & June 26 in Pomona

Conference registration closes May 22! The $75 registration fee includes continental breakfast and a buffet lunch. Administrators, literacy coaches, counselors, and CSU faculty get 50% off registration using the code ERWC50PERCENT. CSU students can register for free using the code ERWCSUFREE.

All are welcome! You don’t have to be an ERWC teacher to attend.

Featured Speakers

- Carol Jago, author of The Book in Question

- Matthew Johnson, author of Flash Feedback

- Jen Roberts, author of Power Up

- Lamar L. Johnson, author of Critical Race English Education

- John Edlund, Professor Emeritus of Rhetoric and Founding Chair of the ERWC Task Force