Editor’s Note: ERWC is delighted to announce a free webinar with Antero Garcia on Thursday, January 18th at 4:30 pm PST. Antero is an Associate Professor in the Graduate School of Education at Stanford University and Vice President of the National Council of Teachers of English. A former English teacher at a public high school in South Central Los Angeles, Antero’s research explores the possibilities of speculative imagination and healing in educational research. He has authored or edited more than a dozen books about the possibilities of literacies, play, and civics in transforming schooling in America. His new book, co-authored with Ernest Morrell, is Tuned-In Teaching: Centering Youth Culture for an Active and Just Classroom.

Register for Antero’s webinar here.

By Chris Lewis, Ph.D.

In 2015, I was deep in my dissertation research, floundering in theory about utopian philosophy and feverishly re-reading M.T. Anderson’s brilliant young adult novel Feed.

As part of my study, I was working with a group of high school seniors reading dystopian novels and talking about youth civic engagement and participation in resistance movements. There had been an increase in dystopian fiction being published for young readers, and I wondered what they were thinking when young characters overthrew the oppressive systems in their respective societies.

I was fortunate to come across Antero Garcia’s (2013) Critical Foundations in Young Adult Literature: Challenging Genres, where he discussed an essential element in all of young adult dystopian (also a feature of many fairy tales) where the adults/parents are incapable of maintaining the society they built. Antero argued,

“It is a powerful transfer of responsibility found in these books: adults cannot rectify the past nor can they correct the future. It is up to the students in our classrooms-the students reading these books-to transform society for the better. YA, then, if we are to look for a unifying message across the books, is about teaching youth to grow up and own the future.”

(Garcia 133)

The youth participants in my study agreed with Antero’s assessment throughout their own reflections, noting how the effect of youth-led movements would lead to a more inclusive future and how contemporary classrooms may not be preparing them for this important work.

In the years since my defense, where Antero was a member of my dissertation committee, his scholarship has focused on the importance of youth voice, civic engagement, and humanizing education. His writing continues to inspire me and helps me think through the complexities educators face when youth express their disillusionment in turbulent political times. I am constantly reminded how, without constant reflection on pedagogy and practice, educators might inadvertently disempower youth through our curricular choices or the systems we put in place.

We need more classrooms to be spaces of incubation where our students’ ideas, however outlandish they may seem through an adult lens, have space to grow and flourish. And while there will be times where youth feel helpless and fearful, there is power in radical hope. Antero’s research provides essential practices where teachers and students can engage in this kind of learning that just might change the world for the better.

Interested in some more reading on these topics, check out:

Cammarota, J., & Fine, M. (2008). Revolutionizing education: Youth participatory action research in motion. New York, NY: Routledge.

Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy, and civic courage. Lanham, MD: Rowan & Littlefield Publishers.

Hogg, L., Stockbridge, K., Achieng-Evensen, C, & SooHoo, S. (2021). Pedagogies of with-ness: Students, teachers, voice and agency. Myers Education Press.

Mirra, N., & Garcia, A. (2023). Civics for the world to come: Committing to democracy in every classroom. W. W. Norton.

Mirra, N., Garcia, A., & Morrell, E. (2016). Doing youth participatory action research; Transforming inquiry with researchers, educators, and students. Routledge.

Chris Lewis is a TOSA supporting ELs and a part-time lecturer for a graduate education program. He also serves as the ERWC Social Media Coordinator. His publications include two chapters in Pedagogies of With-ness : Students, Teachers, Voice and Agency: “Who is Listening to Student?” and “Finding Hope Through Dystopian Fiction.” You can follow Chris @chrislewis_10.

Save the Date!

The 2024 ERWC Literacy Conferences will be held June 17 in Northern California and June 25 in Southern California. Please make your calendar. All are welcome!

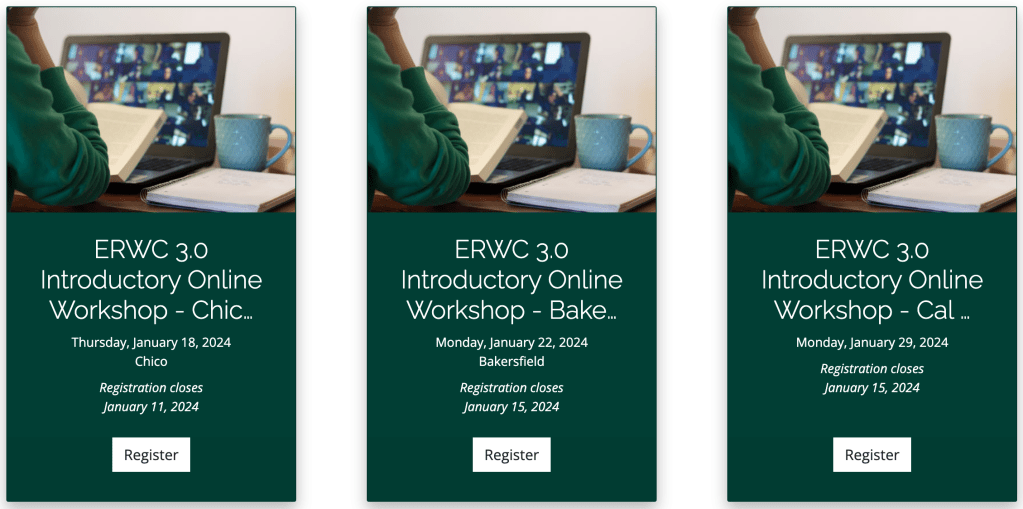

ERWC 2023-24 Literacy Webinar Series:

In the Classroom

All webinars are scheduled for 4:30 pm on a Thursday. Registration is free. Connect with your ERWC colleagues, enjoy top-quality professional learning, and hear ERWC updates.

Antero Garcia: January 18, 2024 at 4:30 pm PST

“Building Student Engagement”

Does your classroom ever feel stuck, or out-of-tune? Meaningful teaching is something educators strive for each day. Educators also know that there is no such thing as a perfect classroom. Despite our best intentions, our classrooms sometimes feel like they’re stuck, or out of tune. In this webinar, Antero Garcia will explain why we should allow students to play an integral role in turning classrooms into spaces for greater engagement and innovation.

Troy Hicks: February 15, 2024 at 4:30 pm PST

“Teaching with Technology”

Interested in using technology more effectively in the classroom? In this webinar, Troy Hicks–an ISTE Certified Educator–will introduce “digital diligence”–an alert, intentional stance that helps both teachers and students use technology productively, ethically, and responsibly. Hear his strategies for minimizing digital distraction, fostering civil conversations, evaluating information on the internet, creating meaningful digital writing, and deeply engaging with multimedia texts.

Looking for an ERWC Workshop?

Find upcoming in-person or virtual ERWC professional learning sessions. ERWC workshops are free to teachers in California!

Please contact Dr. Lisa Benham at lbenhan@fcoe.org for information on ERWC professional learning services outside of California.