By Grace Adcock and Cristy Kidd

October 20, 2025

Picture a student in your classroom who has mastered speaking and listening. You probably saw someone who is actively listening, speaking with confidence, informed with facts and ideas, knows when to speak up and when to make space for others, considers counterarguments, and has audience awareness.

We know, however, that there are barriers keeping students from growing into their potential: anxiety, practice (or lack thereof), past experiences, low confidence and devaluation of their ideas. We must break down these barriers so students can find and use their voice.

Creating Norms and Expectations

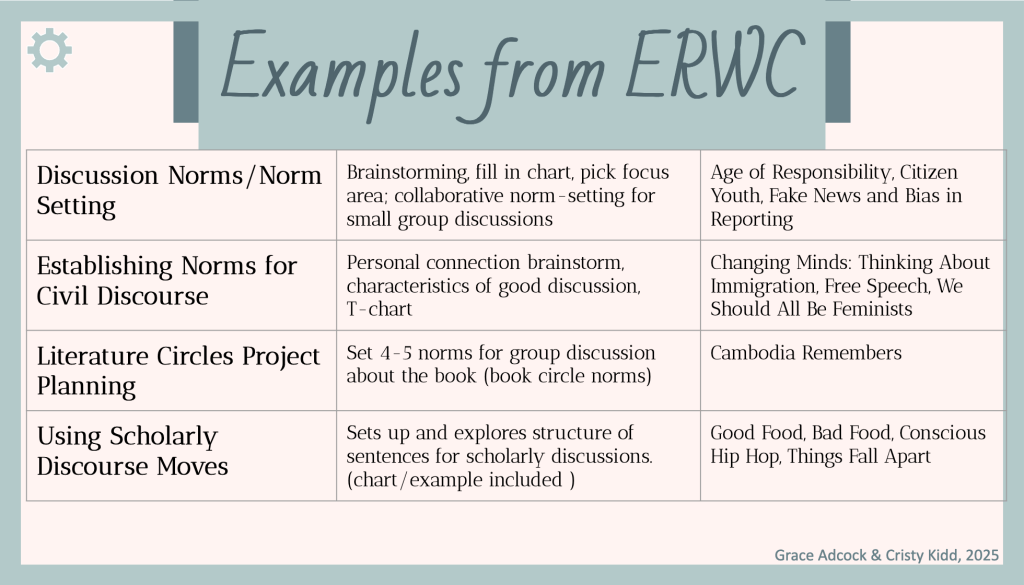

The first step is creating norms and expectations around speaking in your classroom. In the HIST (High Impact Strategy Tool Kit) many options already exist.

We found success in using one strategy, “Discussion Norms/Norm Setting,” as a cornerstone in our classrooms throughout the year to establish all speaking and listening norms. It provides space for students to share in the decision-making process around how discussions will work. Choose the norm setting activity that works best for you, use it early in the year as a foundation for your classroom discussions – revisit and reference it often.

Responding and Modeling

Revisiting norms allows space and time to respond to situations where they have been broken and to model the expected behaviors. It is important to shut down the harmful behaviors that impede a student’s ability to participate through reframing. Making sure students have had a say in the norms makes them easier to uphold. Reminding students their feelings and experiences are shared by others in the room helps build confidence. Modeling that even teachers get nervous or that speaking is not always easy for us helps to reinforce this. There are many examples in ERWC modules where teachers are asked to model and frontload expectations because it works and supports student learning.

“Reminding students their feelings and experiences are shared by others in the room helps build confidence.”

Intentionally Planning

When we think about speaking opportunities we offer students we identify reports, speeches, presentations, and class or group discussions. As ERWC teachers, we spend time considering the activities we will keep or cut, the order in which we will present modules to our students, and when we will teach certain skills, but we don’t often consider how we spiral a progression of speaking and listening.

Once we have set our norms, made efforts to conscientiously break down barriers, the next step is intentionally planning opportunities in the classroom. This starts with the low risk activities we already do: pair share, whip around, single word answers, etc. Not all speaking activities need to be formal; it is imperative to remember that speaking is something students do every day. We must make planned, intentional spaces to support their growth. Just as ERWC modules spiral and follow the arc, we need to spiral and scaffold speaking in our classrooms.

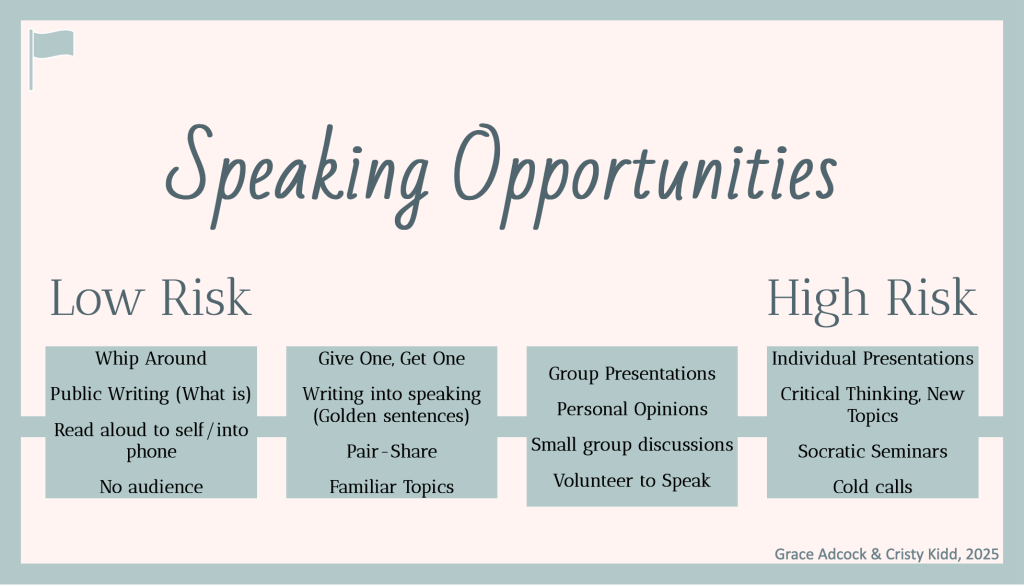

Like Bloom’s taxonomy shows us a progression of complexity of tasks, the image below illustrates a continuum of low-risk speaking opportunities to high-risk ones.

These opportunities, especially at the lower level, are not explicitly delineated or spiraled in the ERWC modules. But we know students need to be guided through a variety of activities. We can’t expect them to be successful at the higher risk activities if they do not have the foundation from the lower risk ones; they work hand in hand to build upon each other. Go back to the ERWC foundation of making decisions: intentionally choose module activities and build a progression.

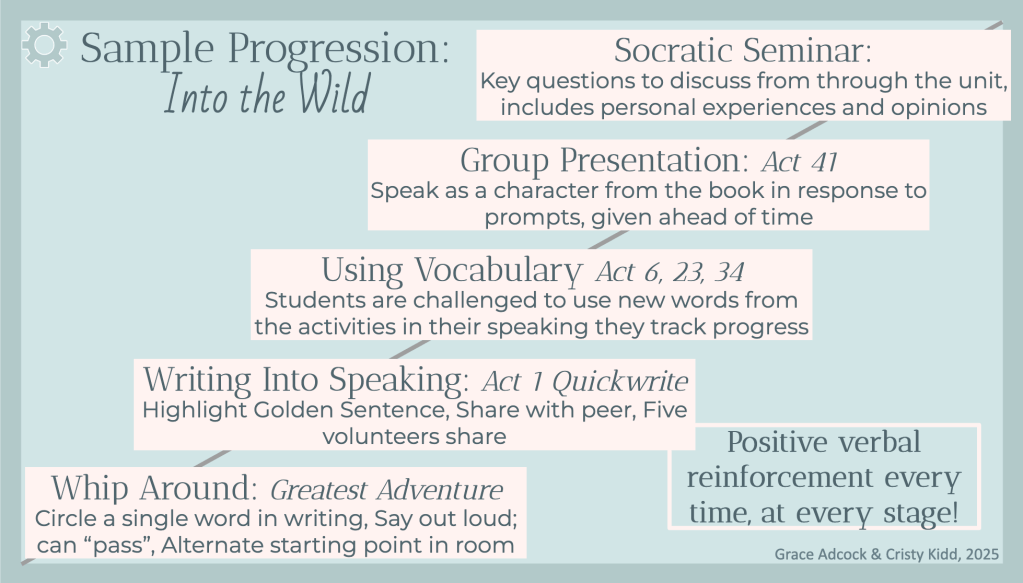

Here is a sample from the ERWC unit “Into the Wild”; We combined activities that exist in the module with our own to carefully plan a progression.

If after all your careful planning and spiraling, you encounter students who are still struggling, remember there are additional options: one-on-one presentations with you or speaking in front of a small group of trusted classmates, for example.

As long as you are providing small opportunities for speaking and normalizing it each and every day you will see growth in student’s confidence and skills. Progress is the goal, it looks different for each student, and it can only be measured individually against their own growth. It is not a competition. Students “win” only when the end game is encouraging them to find and use their voice.

Biographies

Grace Adcock is an educator, wife, mother, and avid baseball fan from Redding, California, where she was raised and her family lives today. She attended CSU Monterey Bay, majoring in Human Communication (HCOM) and minoring in outdoor education and recreation. She then attended CSU Chico for credentialing and graduate studies. She holds a valid Single Subject English, Mild/Moderate Special Education, Multiple Subject, and Reading Specialist credentials, along with her masters in Special Education. Camping, attending baseball games, and traveling take up most of her spare time in the summer and over breaks.

Cristy Kidd is an educator, a scholar, a wife, a reader, and a nerd, born in the San Francisco Bay Area and currently living in Redding. She has been teaching Communication Studies at the community college level for seven years, and has taught high school for five years, first as an English teacher at a traditional site and then at an alternative education independent study school. Outside of academia, she enjoys Dungeons & Dragons, is a certified yoga instructor, and loves live music and musical theatre.